什麼是青少年原發性脊柱側彎 (Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis, AIS)?

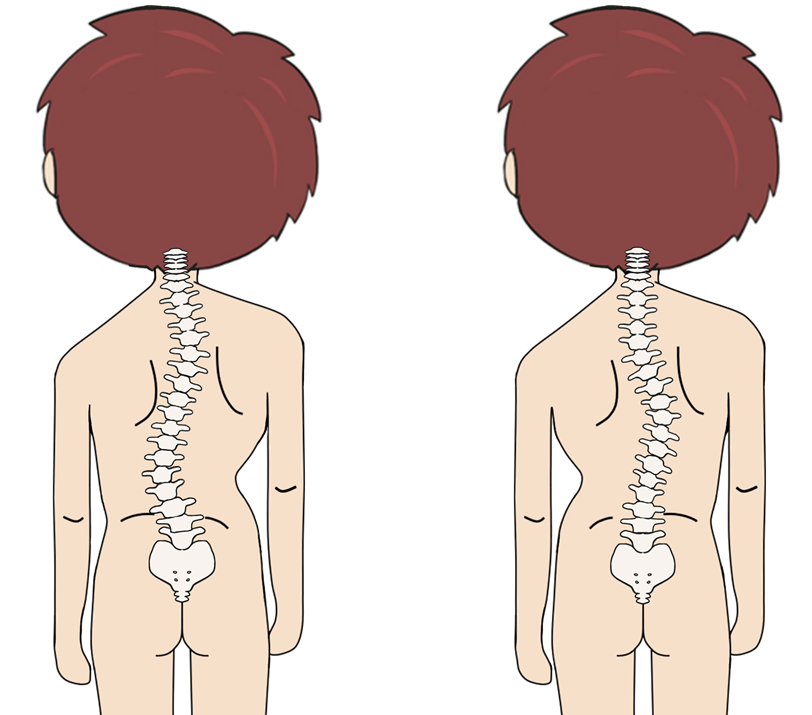

脊柱側彎是指脊骨向左或向右彎曲呈現「C」形或「S」形,青少年原發性脊柱側彎(AIS)是最常見的脊柱側彎類型。全球大約2%至3%的青少年患上青少年原發性脊柱側彎 [1,2]。當中男女比例約為2:8,有家族病史的青少年以及10至15歳的青少年女性有較大的機會患上脊柱側彎 [3]。

青少年原發性脊柱側彎大約在10歲開始,隨著孩子的成長而惡化。大部份患者沒有明顯症狀,部份患者可能會出現各種併發症,從而影響他們的身體、社交和心理健康。主要的併發症包括:一,外觀的影響例如兩肩不平,肋骨突出及軀幹不對稱;二,慢性背痛;三,在一些嚴重的脊柱側彎病例中,患者會因肋骨變形而壓迫肺部和心臟,影響心肺功能 [4,5]。

惡化因素

脊柱側彎惡化的因素,主要包括側彎角度和骨骼發育程度 [6, 7]。

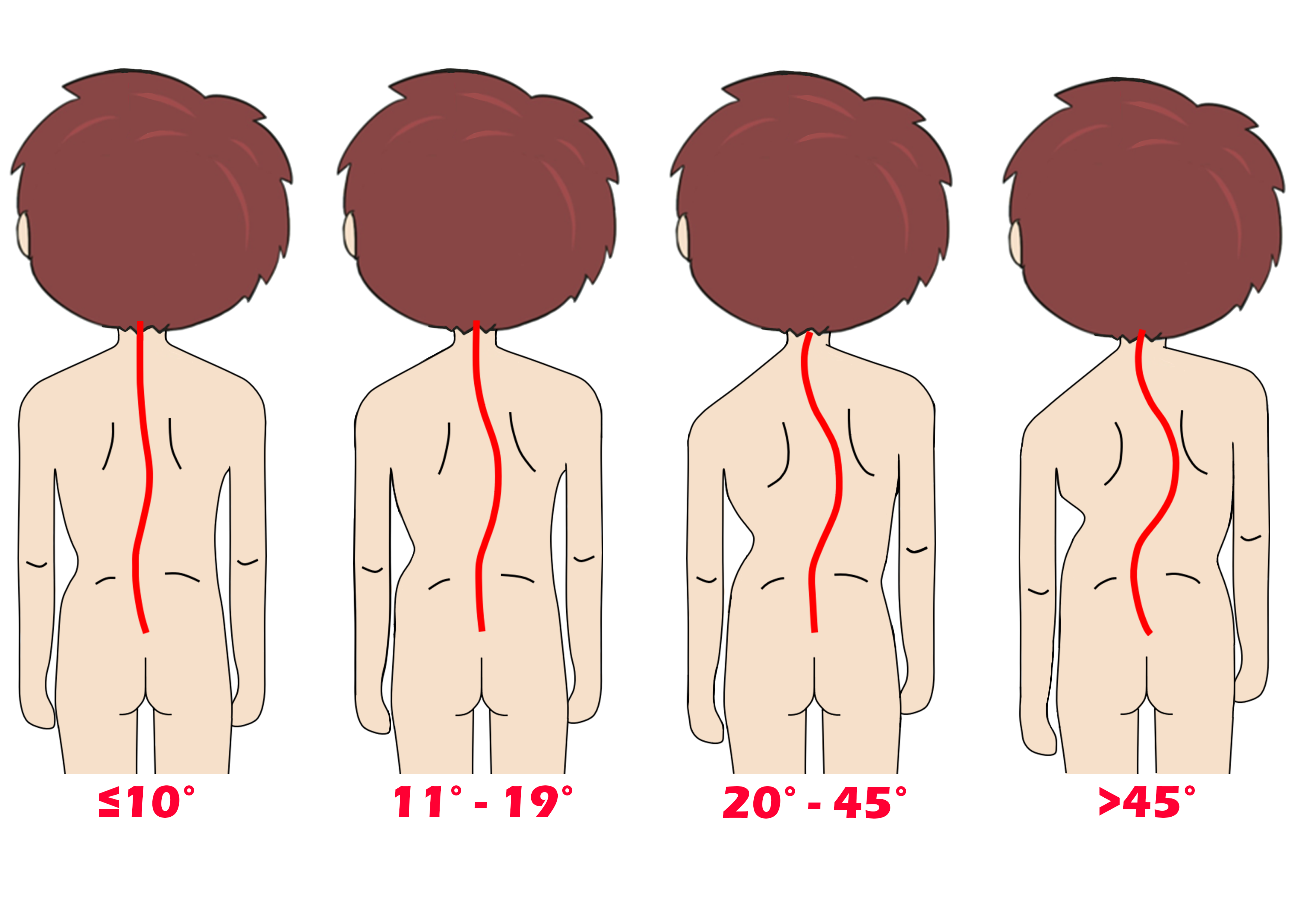

1. 側彎角度

脊柱側彎的嚴重程度取決於脊柱側彎角度(Cobb angle),而脊柱側彎角度是現時全球公認的量度標準 [8]。

多項研究發現,側彎角度愈大,惡化機會也會愈高 [9,10]。根據一項針對186例青少年原發性脊柱側彎的研究,結果顯示側彎的初始角度是側彎惡化的最重要預測因素 [10,11]。

不同的側彎角度

2. 發育程度

脊柱側彎通常在患者發育期間迅速惡化,而發育程度可以透過身高、第二性徵、女性月經期(女性病例)、骨齡(可從手腕X光檢查中檢視)和骨盆生長板的融合程度(Risser’s sign grade)來評估。

在青春期期間,青少年身高會迅速增加,因此測試員可以透過監控他們的身高,以估算其生長潛力。一般而言,女性會在14歲停止發育,而男性則是16歲 [12,13]。

此外,第二性徵的出現,例如陰毛的生長、女性乳房的增大和男性喉嚨的增大等,也表明了青春期的開始 [14]。另外,女性會在出現第一次月經(初經)前發育最快,之後開始減慢,直到初經後大約兩年 [15]。

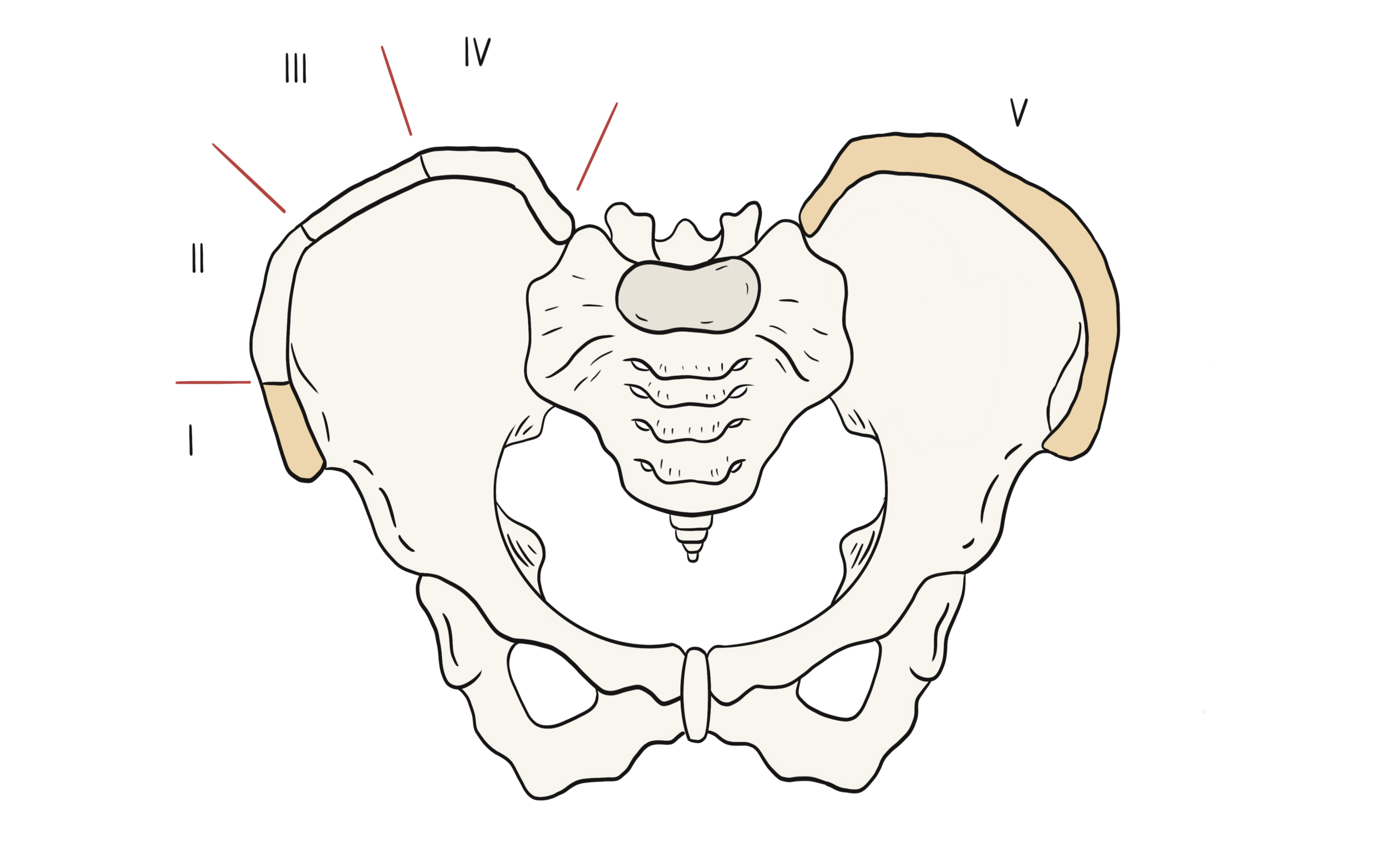

測試員也可根據骨盆生長板的融合 (Risser’s sign grade)來估計個人的骨骼發育程度。Risser’s sign grade共分五級(一級是初始發育,五級是發育完成),級別越高,骨骼發育愈趨成熟,惡化機會則愈小 [16,17]。

骨盆生長板融合分度(Risser’s sign grade)

總括而言,脊柱側彎惡化的風險會隨著大角度的脊柱側彎和較低的發育程度而增加。

參考資料

-

SRS. "Scoliosis Research Society." https://www.srs.org/patients-and-families/conditions-and-treatments/adolescents.

-

J. Dubousset, "Definition of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis," in Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Scoliosis: Springer, 2018, pp. 1-25.

-

J. R. Smith, D. M. Sciubba, and A. F. Samdani, "Scoliosis: a straightforward approach to diagnosis and management," Journal of the American Academy of PAs, vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 40-48, 2008.

-

M. Clinic. "Scoliosis." https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/scoliosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350716.

-

S. H. Service. "Scoliosis." https://www.studenthealth.gov.hk/english/health/health_bsh/health_bsh_sco.html.

-

J. P. Horne, R. Flannery, and S. Usman, "Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: diagnosis and management," American family physician, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 193-198, 2014.

-

Y. P. Charles, J.-P. Daures, V. de Rosa, and A. Diméglio, "Progression risk of idiopathic juvenile scoliosis during pubertal growth," Spine, vol. 31, no. 17, pp. 1933-1942, 2006.

-

J. Cobb, "Outline for the study of scoliosis," Instr Course Lect AAOS, vol. 5, pp. 261-275, 1948.

-

J. Lonstein and J. Carlson, "The prediction of curve progression in untreated idiopathic scoliosis," J Bone Joint Surg, pp. 1061-71, 1984.

-

S. Weinstein and I. Ponseti, "Curve progression in idiopathic scoliosis," The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 447-455, 1983.

-

P. N. Soucacos, K. Zacharis, K. Soultanis, J. Gelalis, T. Xenakis, and A. E. Beris, "Risk factors for idiopathic scoliosis: review of a 6-year prospective study," Orthopedics, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 833-838, 2000.

-

J. Tanner, R. Whitehouse, W. Marshall, and B. Carter, "Prediction of adult height from height, bone age, and occurrence of menarche, at ages 4 to 16 with allowance for midparent height," Archives of disease in childhood, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 14-26, 1975.

-

W. A. Marshall and J. M. Tanner, "Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys," Archives of disease in childhood, vol. 45, no. 239, pp. 13-23, 1970.

-

F. Martini, J. L. Nath, E. F. Bartholomew, W. C. Ober, C. E. Ober, K. Welch, and R. T. Hutchings, Fundamentals of anatomy & physiology. Pearson Benjamin Cummings San Francisco, CA, 2006.

-

B. A. Spear, "Adolescent growth and development," Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, p. S23, 2002.

-

M. Wajchenberg, N. Astur, M. Kanas, and D. E. Martins, "Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: current concepts on neurological and muscular etiologies," Scoliosis and spinal disorders, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 4, 2016.

-

M. Ylikoski, "Growth and progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in girls," Journal of pediatric orthopaedics B, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 320-324, 2005.