Implicit priming with sandhi-undergoing critical targets

This is not a real paper; it is an informal writeup of an unpublished experiment. The research was conducted in 2015-2016 in collaboration with Katrina Connell, while I was at the University of Oxford and Katrina was at the University of Kansas. This report was written in 2022. See My file drawer for an explanation of why I'm recording this. Comments and questions are welcome. —Stephen Politzer-Ahles

1 Introduction

Politzer-Ahles and Zhang (2014) used the implicit priming paradigm to test how words that undergo Mandarin third tone sandhi are represented during speech production. Third tone sandhi is the phenomenon whereby a Mandarin morpheme normally pronounced with Tone 3 (hereafter "T3") instead gets pronounced with something like Tone 2 (hereafter "T2") if it's followed by another Tone 3. For example, 水 (shui3 "water") is normally pronounced with T3, but in the compound word 水果 (shui3guo3 "fruit") it actually gets pronounced with T2.

We tested how people encode these kinds of words for production using a variant of the implicit priming paradigm (Meyer, 1990). In implicit priming, participants memorize a set of words to produce when cued; for example, they might memorize the word pairs signal–beacon, science–beaker, and dog–beagle, and then perform a task in which they have to say beacon whenever they see the word signal, say beaker whenever they see science, etc. The key finding is that people respond faster when all the words they have to produce start with the same syllable (as in the above example), and slower if one of the words starts with a different syllable. For example, if instead of dog–beagle, the set of words instead included poet–beatnik, participants would respond slower across the board, because beatnik starts with a different first syllable ([bit]) than the other words participants have to produce ([bi]). Crucially, it's not just that people produce beatnik more slowly than they produce beagle; rather, they even produce beacon and beaker more slowly when they're randomly intermixed with beatnik than they produce these exact same words when they're randomly intermixed with beagle. In other words, when all the words to be produced start with the same syllable, the participant can pre-prepare the articulatory code for that syllable even before they know which word they need to say on a given trial; on the other hand, when one of the words is an "odd man out" that starts with a different syllable, this "spoils" participants' ability to pre-prepare the articulatory code, causing slower reaction times across the board.

In Politzer-Ahles and Zhang (2014) we used this paradigm to look at tone sandhi. Specifically, we had participants memorize and produce sets of T3-initial Mandarin compound words, which could also include an extra "odd man out" word that may or may not spoil the participants' ability to pre-encode the first syllable. An example stimulus set is shown in the table below.

| Homogeneous | Tonally heterogeneous | Sandhi | Unrelated |

|

鄙视 bi3shi4 比赛 bi3sai4 彼岸 bi3an4 笔名 bi3ming2 |

鄙视 bi3shi4 比赛 bi3sai4 彼岸 bi3an4 鼻孔 bi2kong3 |

鄙视 bi3shi4 比赛 bi3sai4 彼岸 bi3an4 笔挺 bi3ting3 |

鄙视 bi3shi4 比赛 bi3sai4 彼岸 bi3an4 画家 hua4jia1 |

We were interested in the reaction times for the first three words, which are the same across all four conditions shown above. We expected that these words would be produced fastest in the "homogeneous" condition (where the extra fourth word starts with the same syllable as the critical three words) and slowest in the "unrelated" condition (where the extra fourth word starts with a syllable that has completely different segments and tone than the critical three words). We also expected that reaction times for these same words would be slow in the "tonally heterogeneous" condition, where the fourth word starts with a different tone than the critical three words. The crucial test is how fast these words are produced in the "sandhi" condition. In this condition the first syllable of the extra fourth word has T3 (the same tone as the critical three words) underlyingly, but because of tone sandhi this syllable actually gets pronounced as T2. Thus we wanted to see if phonological encoding (as indicated by participants' reaction times when producing the three critical words) would be based on the underlying T3 or on the surface T2. If it's based on the underlying T3, reaction times should be fast, like in the "homogeneous" condition. On the other hand, if it's based on the surface T2, reaction times should be slow, like in the "tonally heterogeneous" condition. In other words, this sandhi condition is "homogeneous" at the underlying level but "heterogeneous" at the surface level, and we wanted to see which level would drive reaction times in the implicit priming task.

In our experiments, this sandhi condition was produced slowly, i.e., like a heterogeneous condition. In other words, reaction times were driven by the surface T2 form (at which level the set of four stimuli was heterogeneous) rather than by the underlying T3 form (at which level the set of four stimuli was homogeneous). We also confirmed this explanation in a follow-up experiment where the three critical words were T2, such that the odd-man-out sandhi word makes the set heterogeneous at the underlying level but homogeneous at the surface level, so the predictions for that situation are the opposite of the predictions when the critical words are T3. When the critical words were T2, the sandhi set yielded fast reaction times, like a homogeneous set. In short, the phonological encoding that is reflected in the implicit priming paradigm seems to rely on the surface forms rather than the underlying forms, so that a set made up of T2s and sandhi tones is treated as "homogeneous" and a set made up of T3s and sandhi tones is treated as "heterogeneous".

One criticism that occasionally came up for this experiment was that we never actually analyze reaction times to the sandhi-undergoing word; we only look at reaction times to the critical words, which don't undergo sandhi. I never found this criticism very troubling, because the experiment was specifically designed to allow us to make inferences about the encoding of the sandhi word based on how the presence of that word influences the reaction times for other words. Nonetheless, several years later Katrina and I decided we would try to modify the experiment to let us look at reaction times for the sandhi words themselves (and as an added bonus, that would let us try to conceptually replicate the original findings).

2 The present study

The change we made for this experiment was very simple: we just let sandhi words be the critical words, and unambiguously T2 or T3 words be the odd-man-out words. This would let us test pretty much the same conditions as the original study, but measure the reaction times on the sandhi words (which are identical across conditions) rather than on non-sandhi words. An example stimulus set is shown below (the condition labels refer to the characteristics of the odd-man-out word, rather than of the full set):

| Sandhi | Tone 2 | Tone 3 | Unrelated |

|

保守 bao3shou3 保姆 bao3mu3 保险 bao3xian3 宝岛 bao3dao3 |

保守 bao3shou3 保姆 bao3mu3 保险 bao3xian3 雹雨 bao2yu3 |

保守 bao3shou3 保姆 bao3mu3 保险 bao3xian3 宝剑 bao3jian4 |

保守 bao3shou3 保姆 bao3mu3 保险 bao3xian3 温暖 wen1nuan3 |

Here, the critical words are all words that undergo tone sandhi, such that their first syllables are all T3 underlyingly but T2 at the surface. The homogeneity or heterogeneity of each set is determined by the extra fourth word in each set. We expect reaction times to be slowest in the "unrelated" condition (where the odd-man-out word starts with a completely different syllable than the other words in the set) and fastest in the "sandhi" condition (where the odd-man-out word is also a sandhi-undergoing word, and thus starts with the same syllable as the other words both underlyingly and at the surface). Based on the results of the previous study, we further expected that reaction times would be fast (comparable to the sandhi condition) in the "Tone 2" condition, where the set is homogeneous at the surface but not underlyingly, and would be slow (comparable to the unrelated condition) in the "Tone 3" condition, where the set is homogeneous underlyingly but not at the surface.

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

Data were collected from 25 native speakers of Mandarin in Kansas. Three participants were excluded from further analysis because they didn't provide data for all critical blocks, so the final analysis included data from 22 participants. All participants provided their informed consent to participate in the study and received payment, and all methods were approved by the Human Subjects Committee of Lawrence at the University of Kansas.

3.2 Materials and design

Four sets of critical stimuli, like the one in the above table, were prepared, as well as one block of four practice stimuli and four blocks of four filler stimuli. The practice block was like an "unrelated" block (i.e., it included three target words with the same initial syllable and one target word with a different syllable). As for the filler blocks, two included four words that all had different tones and segments in their initial syllables; one was like the critical and practice "unrelated" blocks; one was like a tonally heterogeneous block but did not involve tone sandhi (three of the critical words began with fu4 and one with fu3); and one was homogeneous but did not involve tone sandhi. The full stimulus list is available in a spreadsheet included at the bottom of this page.

3.3 Procedure

The blocks were presented in a fixed order, but the correspondence between conditions and stimulus sets was Latin squared. That is to say, the first block (after practice) was always the set of di targets, but for some participants it was in the sandhi condition and for some participants it was in the T2 condition, etc. The second block was always an unrelated filler set; the third block was always the set of cai targets, but presented in different conditions for different participants; and so on and so forth.

If I recall correctly, the procedure within each block was the same as the procedure of Politzer-Ahles and Zhang (2014). The experiment was implemented in Psychopy.

3.4 Analysis

Speech onsets were manually measured in Praat and coded by us for correctness, the same as in Politzer-Ahles and Zhang (2014).

4 Results

The reaction time data are included at the bottom of this page. Two participants were removed because they did not complete one or more critical blocks, and one more participant was removed because they produced the wrong words in one critical block or something like that (I'm honestly not totally sure, I just see a note I left in the Excel spreadsheet 6 years ago saying to exclude that entire block for that participant).

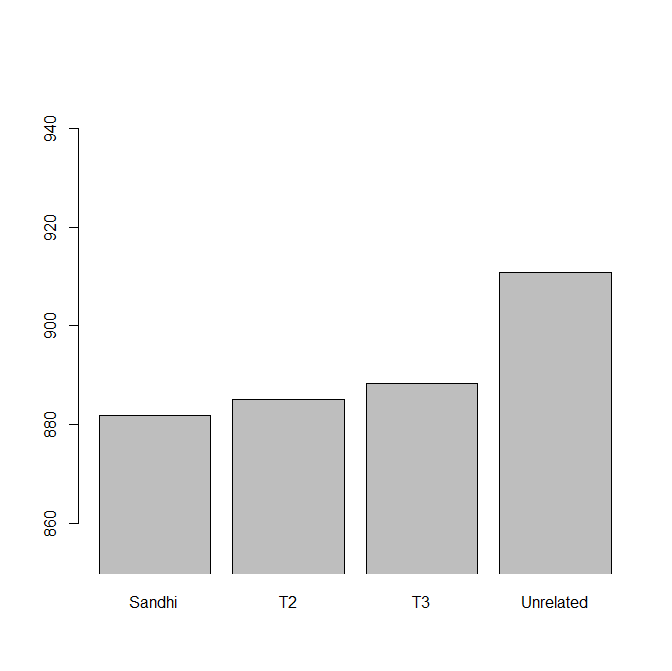

Figure 1 shows the mean RTs across conditions, and Figure 2 shows the by-participant priming effects for each condition. The sandhi condition elicited responses 29ms faster than the unrelated condition; the Tone 2 condition, 26ms faster than the unrelated condition; and the Tone 3 condition, 23ms faster. As shown in Figure 2, these effects were not super robust across participants, and there is no clear trend for the priming in any one condition being bigger than the others. While I guess there is a slight numerical trend in the direction we predicted (the sandhi condition is indeed the fastest, and the T2 condition does indeed have a teeny tiny bit more priming than the T3 condition), the pattern is not at all striking (i.e., doesn't pass the inter-ocular trauma test) and not obviously matching what we expected (e.g., we predicted that the T3 condition would pattern like the unrelated condition, but it's actually much closer to the sandhi condition and the T2 condition).

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

We also tried a bunch of other p-hacky data wrangling (such as regressing out the effect of block order) but the overall pattern remained the same; no matter how you look at it, it looks like the sandhi, T2, and T3 conditions were all primed relative to the unrelated condition, and all primed to similar extents.

5 Discussion

The results don't really look like what we predicted. They look more like the results of Chen & Chen 2014 (in the same volume as Politzer-Ahles & Zhang 2014); they did an implicit priming study very similar to Politzer-Ahles and Zhang, but they found that T2, T3, and sandhi all pattern about the same (e.g., in a set of words that start with T3, neither T2 nor sandhi tones spoil the priming), presumably because T2 and T3 are so phonetically similar. (To really see if this is the case for the present study, one would need to redo this study with an additional "heterogeneous" condition whose odd-man-out word starts with T1 or T4, to see if that triggers reaction times as slow as the reaction times for the 'unrelated' block.)

I guess further research could be done to try to see what's going on across these studies (see Politzer-Ahles & Zhang for more review of a few other implicit priming studies on sandhi that got a bunch of conflicting results). Maybe there is some hidden moderator that explains why some T3 and T2 are different enough in some studies to spoil priming but not in others. Or maybe some of these findings are just Type 1 or Type 2 errors, and some high-powered pre-registered replications could clear the air. But I kind of suspect that doing any of this stuff is not worth the trouble. The heterogeneity of results on this topic (Politzer-Ahles & Zhang, Chen & Chen, two other studies that Politzer-Ahles & Zhang discuss, and now this one) makes me have little faith in the robustness of this paradigm itself, at least as it is applied to tone sandhi research. Maybe I'm just a quitter, but tbh this study (as well as my small failed attempt around 2014 to do implicit priming in MEG/EEG with a simple English manipulation) has made me lose faith in the utility of the implicit priming paradigm for looking at tone sandhi.