MMN experiments on lexicality of sandhi-derived allomorphs in Mandarin

This is not a real paper; it is an informal writeup of an unpublished experiment. The research was conducted in 2014 at Peking University (while I was supported by New York University Abu Dhabi) and this report was written in 2015. See My file drawer for an explanation of why I'm recording this. Comments and questions are welcome. —Stephen Politzer-Ahles

1 Introduction

The purpose of this experiment was to examine storage vs. composition/decomposition of second-tone (T2) allomorphs of underlyingly third-tone (T3) syllables in standard Mandarin. I focused on T2 syllables like ká. This syllable does not exist as a citation form of any character or morpheme in standard Mandarin pronunciation. The T3 syllable kǎ, however, does exist, and because of T3 sandhi, in some contexts it is pronounced as T2 ká (e.g., 电脑卡死了). Weiner & Turnbull (2013, poster at LSA annual meeting) give evidence that these syllables are responded to more slowly than unambiguous words in lexical decision. The present experiments meant to use neurophysiological recordings to test whether a these syllables—T2 allomorphs like ká, which do not exist as citation forms but are attested as a surface variant of a T3 syllable—are stored in the lexicon or not.

These experiments used the mismatch negativity (MMN) component of event-related potentials to examine this question. A line of research in several languages has found that, when sounds corresponding to words or nonwords are presented in an oddball paradigm, a more negative MMN is elicited when a word is the deviant than when a nonword is (Korpilahti et al., 2001; Pulvermüller et al., 2001; Kujala et al., 2002; Shtyrov & Pulvermüller, 2002; Pulvermüller et al., 2004; Pettigrew et al., 2004; Gu et al., 2012; see review in Pulvermüller & Shtyrov, 2006; see also Endrass et al., 2004 and Pettigrew et al., 2004b). (Note that in this paradigm, it is argued that what matters is the lexicality of the deviant stimulus, not that of the standard stimulus; see Shtyrov & Pulvermüller (2002).) Thus, the overall design of the experiments described here was to measure the MMN response to ká when it was embedded in a deviant stimulus in contrast to some standard stimulus, and to compare it to unambiguous word and unambiguous nonword controls to see whether it elicits a comparatively large or small MMN effect. If it elicits a large MMN effect, that would suggest that there are stored cortical representations of allomorphs like these even though they don't correspond to real citation forms; if it elicits a smaller MMN effect than unambiguous real words, that would suggest that the cortex has abstract lexical representations and does not necessarily keep stored representations of everything a speaker hears in the language (since a speaker hears ká from time to time but perhaps does not store a lexical representation with this form).

2 Experiment one

The first experiment included the following blocks:

- Sandhi experimental conditions:

- kǎ kǎ kǎ → ká (deviant is a sandhi-derived allomorph)

- ká ká ká → kǎ (deviant is an existing citation form)

- Non-sandhi control conditions:

- píng píng píng → pǐng (deviant is unambiguously a nonword—pǐng does not occur as a citation form, and there is no alternation in standard Mandarin phonology that changes another tone to T3)

- pǐng pǐng pǐng → píng (deviant is an existing citation form)

For each deviant, the MMN was calculated by subtracting the ERPs to the same (acoustically identical) word in the block where it was used as a standard, from those in the block where it was used as a deviant. The experiment did not show the expected lexicality effects in the control comparison (i.e., deviant píng did not elicit more a more negative MMN than deviant pǐng, and thus the data from this experiment could not be used to evaluate any questions about lexicality in the sandhi case. Other effects of potential interest, however, were observed, and these are currently under further investigation; therefore, this experiment will not be discussed in further detail here.

3 Experiment two

The reason for the lack of lexicality effect in experiment one may have been that tone-based effects overshadowed lexicality-based effects. Notice that the conditions being compared (for instance, the two non-sandhi control conditions) differ in the direction of the tone change: the nonword deviant occurs in a block where the contrast is between a frequent T3 stimulus and an infrequent T2 stimulus, whereas the word deviant occurs in a block where the contrast is the opposite, between a frequent T2 stimulus and an infrequent T3 stimulus. While I had no a priori prediction that this would matter, it could have, and thus could have masked lexicality effects. (For potentially related discussion of asymmetrical effects on vowel cognition, see Polka & Bohn, 2003, 2011.) Thus, this experiment tested similar stimuli, but in a design that held direction of tone contrast constant across the blocks that would be directly compared. The design was as follows:

- Sandhi experimental conditions:

- pá pá pá → ká (deviant is a sandhi-derived allomorph)

- pǎ pǎ pǎ → kǎ (deviant is an existing citation form)

- Non-sandhi control conditions:

- kǎ kǎ kǎ → pǎ (deviant is a nonword)

- ká ká ká → pá (deviant is an existing citation form)

Another design attempting to address this same issue was run concurrently, see experiment three below.

3.1 Participants

Eleven participants who grew up (took at least elementary and middle school) in Beijing. Two were removed because of excessive artifact in their recordings.

3.2 Materials and design

A male speaker from the same population spoke the stimuli (for both this and the next experiment) in a random order. For each syllable used in the design, I selected the best token out of several repetitions, excluding tokens with any other noises and excluding T3 tokens with vocal fry. This yielded four tokens for the experiment. For each pair kǎ~pǎ and ká~pá, the durations were normalized so as to keep both the stop-vowel ratio and the overall duration the same for both tokens. The intensity of all the stimuli was normalized to 75 dB.

3.3 Procedure

Stimuli were presented in for separate blocks. Each block included 850 standards and 150 deviants. Each block began with between 20 and 28 standards, after which the stimuli were pseudorandomly presented such that between 2 and 10 standards intervened between each deviant. The inter-stimulus interval was set to 500 ms. The four blocks were presented in a unique random order for each participant. During each block, the stimuli were presented binaurally with tube earphones while participants watched a silent movie with Chinese subtitles or read a book or article in Chinese. Participants were given breaks during each block. At the end of each session, the participant was given a paper-and-pencil survey to verify the expected lexicality of the stimuli: the participant was shown the stimuli of this experiment and experiment three (see below) written in Hanyu Pinyin, and asked to write down any characters she could think of that had that pronunciation. Only participants who wrote down characters for pá and kǎ, and not for pǎ and ká, were included in subsequent analyses.

Most participants completed both this experiment and Experiment three (below) in the same session. For those who did, about half completed this experiment first and about half completed experiment three first.

3.4 Data acquisition and analysis

The EEG was continuously recorded using an elastic electrode cap (Brain Products, Munchen, Germany) containing 64 tin electrodes organized according to the 10-20 system. Additional channels were placed above the right eye and at the outer canthus of the left eye for monitoring vertical and horizontal electro-oculograms (EOGs), respectively. An electrode placed on the tip of the nose served as the reference during data acquisition, and AFz served as the ground. Impedances were kept below 10 kΩ. The recordings were amplified using a Brain Products Brainamp amplifier with a bandpass from 0.016 to 100 Hz, and digitized at a sampling rate of 500 Hz.

Data were processed offline using EEGLAB. Bad channels were interpolated and then the data were re-referenced to the average of both mastoids. The continuous data were filtered from 0.5 Hz to 30 Hz, and then segments from 200 ms before to 500 ms after the onset of each syllable were extracted. Epochs were baseline-corrected using the -100 to 0 ms pre-stimulus interval. Trials in which absolute voltage exceeded ±75 µv in the -150 to 400 ms interval were excluded from analysis, as were the first series of standards in each block, the first deviant in each block, and the first standard after each deviant. The minimum number of trials retained in any condition was 37. MMN difference waves were made by subtracting the averaged ERP for a given syllable when it was used as a standard from the ERP to the same syllable when it was used as a deviant.

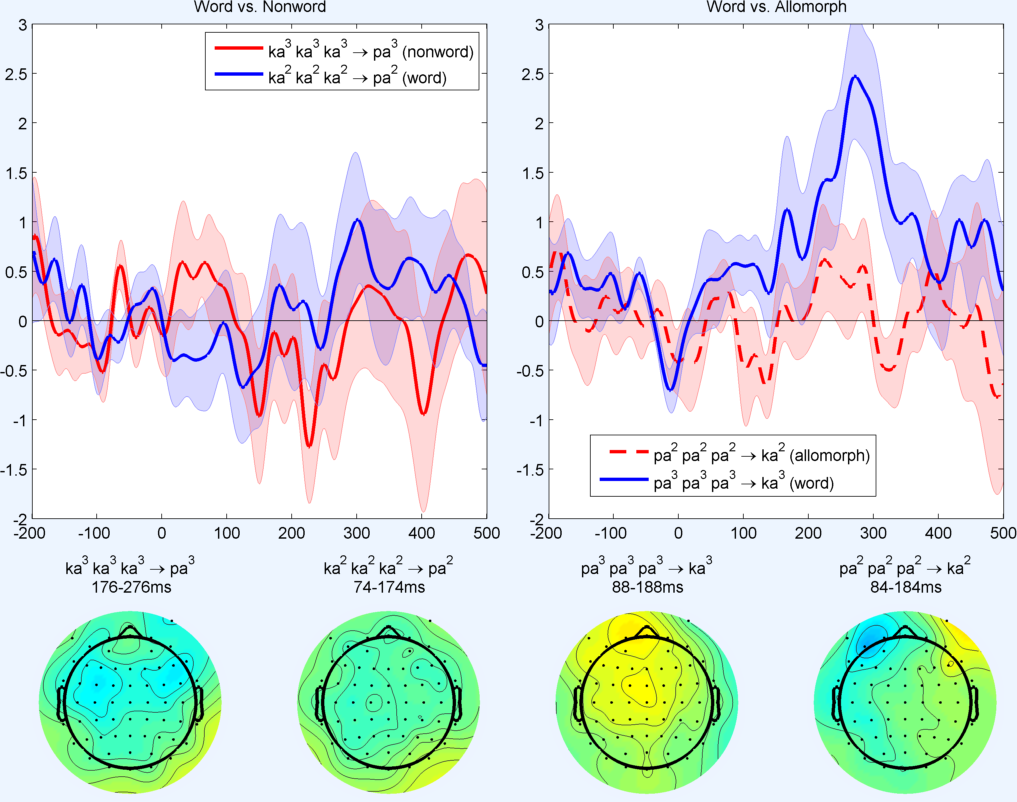

3.5 Results

MMN waveforms at Fz are shown below, with ribbons representing 2 times the standard error of the mean, and topoplots centered at peaks (100 ms windows surrounding the minimum in the 100–500 ms window for each MMN condition). Note that negative is plotted down.

It is evident that there is no robust MMN pattern whatsoever, and certainly no robust lexicality effect between different MMN conditions. The pattern of results remains the same when looking at different electrodes, and when correcting ocular artifacts with ICA before processing.

4 Experiment three

It is not clear why experiment two failed to show robust MMN effects. While experiment two was also being run, I also (mostly concurrently) ran another experiment, which used yet another modification of the design to attempt to avoid asymmetries in the direction of the contrast being tested (see the introduction to Experiment Two above for an explanation of this problem). In this design, every block tested the exact same contrast (a contrast between the dipthong ai and the monopthong a), while differing in terms of the lexicality of the deviant:

- Sandhi experimental conditions:

- kái kái kái → ká (deviant is a sandhi-derived allomorph)

- kǎi kǎi kǎi → kǎ (deviant is an existing citation form)

- Non-sandhi control conditions:

- pǎi pǎi pǎi → pǎ (deviant is a nonword)

- pái pái pái → pá (deviant is an existing citation form)

4.1 Participants

Eleven participants who grew up (took at least elementary and middle school) in Beijing. Most were the same participants who completed experiment two, completing this experiment in the same recording session. Two participants were removed because of excessive artifact in their recordings.

4.2 Materials and design

The good tokens were selected out of the recording (see section 3.2). From these tokens, I cut out individual individual tokens of k, p, á, ǎ, ái, and ǎi tokens. The consonants were duration-normalized, as were the vowels. Next, the pitch tracks from different vowels were overlaid onto the same vowel, so that the resulting vowels á and ǎ differed only in pitch, not in any other properties (and likewise for ái and ǎi). These various segments were spliced together to create the eight critical tokens (four standards and four deviants), and amplitudes were normalized to 75 dB.

4.3 Procedure

Procedure was the same as in experiment two.

4.4 Data acquisition and analysis

Data analysis was the same as in experiment two, with the exception that MMN difference waves were computed by subtracting ERPs to the standard in one block to ERPs to the deviant in the same block. For instance, ká – kái. The minimum number of trials retained in any condition was 34.

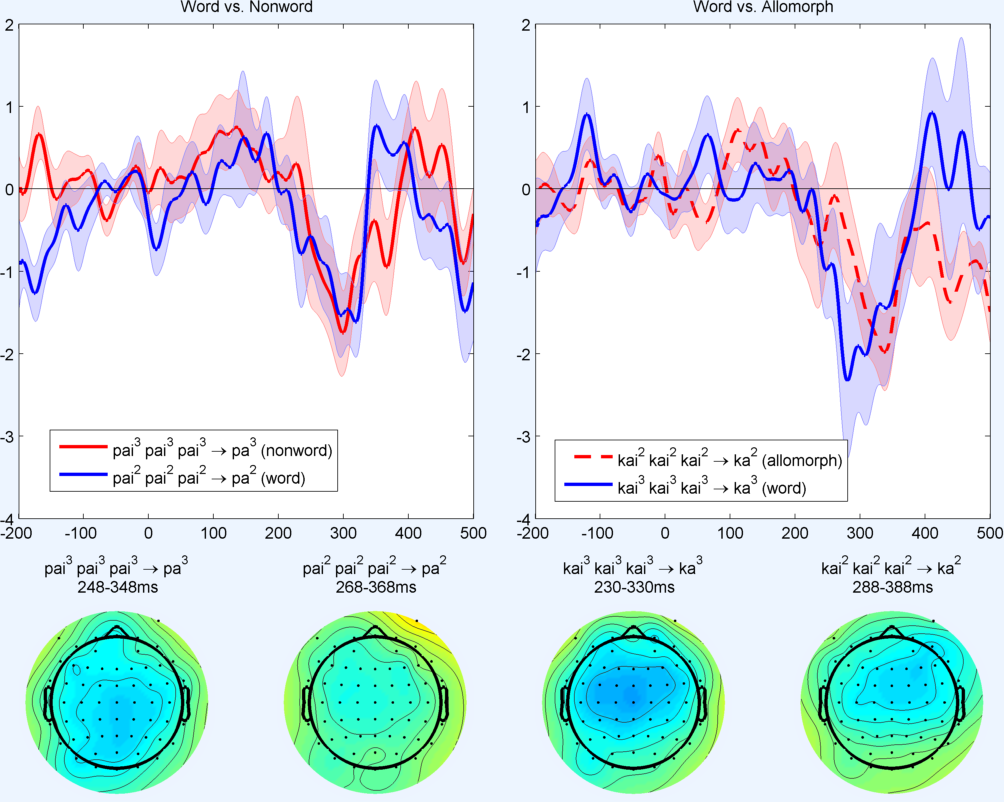

4.5 Results

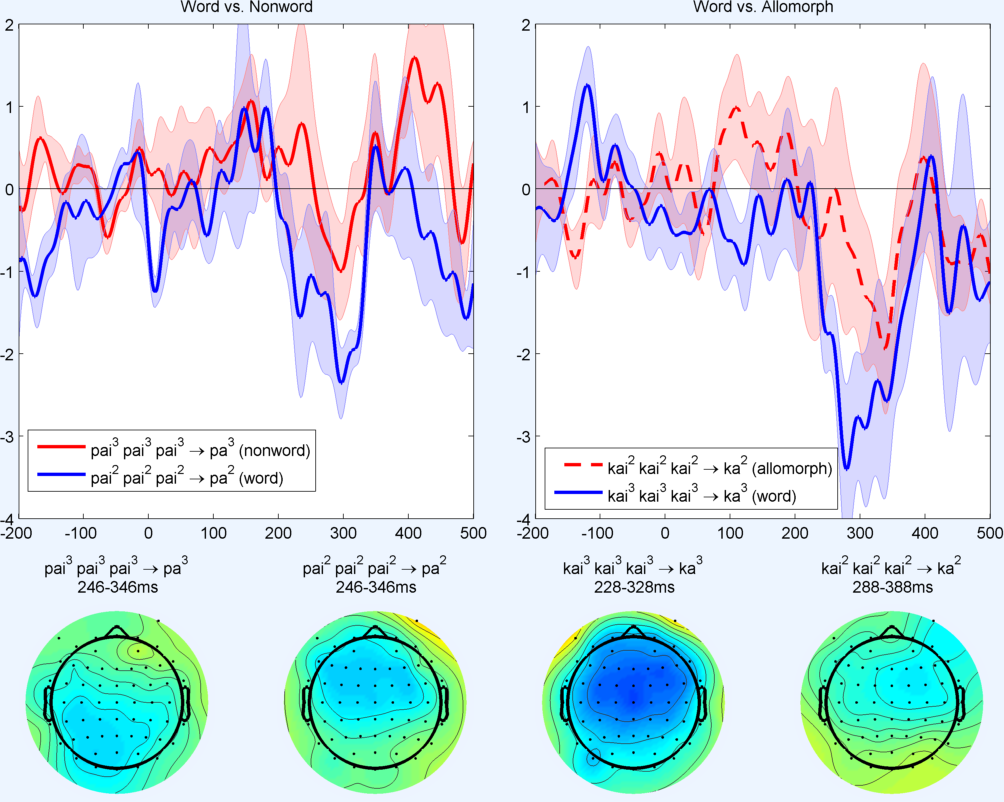

Below I again show MMN waves at Fz, with ribbons representing two times standard error and topoplots centered on the MMN peaks. These data were first artifact-corrected with ICA. (The data without ICA show a similar pattern, although the lexicality effect in the exploratory analysis described below is smaller; the version of this figure without ICA is available here and the version of the next figure without ICA is available here.)

This time, MMN effects are at least evident across conditions. However, it is clear that there is no lexicality effect between the MMNs for the two control conditions on the left. As an exploratory analysis, I restricted the analysis to participants who on an individual level showed clean MMN effects (averaging across all deviant conditions and across all standard deviations). This kept just 5 participants in the analysis. The grand-average waveforms for that subset of participants is shown below. This subset of participants does indeed show the expected lexicality effect in the control conditions (a more negative MMN for the word pá than for the nonword pǎ. Crucially, observing a lexicality effect in the control conditions allows us to look at the effect in the experimental, sandhi conditions. Here there are also more negative MMNs for the real word than for the sandhi-derived allomorph. This could be taken as evidence that sandhi-derived allomorphs aren't lexically represented at the cortical level (although this is, of course, a very post-hoc analysis, and this effect only came out in one out of several experiments).

While the results of this final post-hoc analysis are enticing, the bigger question is why the lexicality effects are so weak in this series of experiments. Experiments one and three did not show lexicality effects in the omnibus analyses, and experiment two did not robustly show MMNs at all. See Pettigrew et al. (2004a) for discussion of factors that can contribute to failure to see effects in this paradigm.

Supporting files

- EEG data (at any stage of analysis) available on request

- Audio stimuli for experiment two (wavfiles, 0.111 MB .zip)

- Audio stimuli for experiment three (wavfiles, 0.215 MB .zip)