The Stroop task you carried out is used to measure people's executive function.

Executive function is the part of your mind that's responsible for controlling what other parts of your mind are doing. It involves many different (but related) things, such as attention control (choosing what to focus your attention on), inhibition (stopping yourself from thinking or doing certain things), switching (changing to one task or concept after you've been settled in a different task or concept), planning, etc. To remember what executive function is, you can remember the word "executive"; it's the same word that you see in, e.g., CEO (a CEO of a company is the "chief executive officer"), or "Chief Executive" of a country.

Just as some people have high working memory capacity and some people have lower working memory capacity, different people may also have different levels of executive function ability. Some people might be very good at focusing their attention, inhibiting certain behaviours, etc. Other people might not be very good at it. Again, you can make a parallel with countries; some countries might have a Chief Executive who has a lot of control (or even is a dictator), whereas some countries have a Chief Executive that can't do much (whether it be for constitutional reasons—i.e., that the country's government system gives more power to the legislature than to the executive— or for political or personal reasons, i.e. that the person just can't or doesn't want to do things).

Why is the Stroop task related to executive function? What do you have to do to succeed in the Stroop task?

For the 'neutral' section of the Stroop task, you don't really need to do anything special; you just see the colour and name it. But for the 'incongruent' section, you have to do a lot of things related to executive function. You have to focus your attention: when you see a word like red, you have to force yourself to pay attention to the colour, not the actual word. And you have to inhibit yourself; your most natural reaction might be to say "red", but you have to stop yourself from doing that, so that you can say the correct answer, "blue".

The assumption, therefore, is that if people have very good executive function ability, they should be very good at doing the incongruent task, and thus their 'incongruent' speed won't be much slower than their 'neutral' speed. On the other hand, if people have relatively poor executive function ability, they should not be very good at doing the incongruent task, so their speed in the incongruent task will be much slower than their speed in the congruent task.

The version of the Stroop task that you did is called the "colour-word Stroop task", and it's the most famous one. But there are other versions, too. It doesn't have to use colours and words; you can make a Stroop task any time you have a situation where the participant has to focus on one piece of information to make the correct response, and ignore another piece of distracting information. For example, there's another version of the Stroop task called the "size Stroop task", where people read words like this:

大--------------------- 小

Or there's one of my personal favourites, the swear-word Stroop task. People usually get a little distracted, and slow, when trying to name the colours in words like the example shown below. Why might that happen?

shit fuck balls piss asshole bitch cock

(That's an English version of the swear-word Stroop task. I don't know if anyone has done that kind of experiment in Cantonese; Cantonese would have lots of swear words to choose from!)

For another example of executive function in action, watch the below video. Don't skip to the end of the video, and don't read the rest of the text on this page before watching the video; don't be a cheater! Try the test shown in the video, and then read on.

Did you see the gorilla? When I try this test in class, usually about half of people don't see it!

(If you're great at paying attention and this video was too easy for you, or if you just have already seen it, then you can try this more difficult one instead: The Monkey Business Illusion.)

When people realize that they didn't see the gorilla, sometimes they feel bad. I hear people say things like, "Oh my god, am I stupid? How did I miss something so obvious?"

But are people who miss the gorilla really stupid? Why do you think someone might not notice the gorilla? What does it have to do with executive function?

Remember that when you watch this video, you're supposed to pay attention to the people in white. The gorilla is all black. So you might not notice the gorilla, because you're focusing so closely on the people in white shirts. In other words: if you didn't see the gorilla, it might be because your executive function is so good. Maybe you're so good at maintaining focus and controlling your attention, that you didn't notice even the very obvious gorilla. So, if you didn't see the gorilla, you shouldn't feel stupid; you should feel proud of how good your executive control is!

In the section about working memory, I didn't say much about how working memory is needed in language processing; we already saw a detailed example about working memory in the "Introduction to psycholinguistics" module.

But what about executive function? Why might executive function ability influence our language comprehension?

Example 1. Demonstratives

Most languages have demonstratives, which are words like this and that. (What are some demonstratives in your language?)

What's the difference between this and that? How do you know which is which? If there are two books on the table, and you want to tell your study partner which book has the answers they need, you can say "It's in this book" or "It's in that book"; how do you know which one to say?

The main difference between this and that is related to speaker proximity. (There are some other differences as well, but we'll ignore them for now and focus on the proximity issue.) This is sometimes called a "proximal" demonstrative, and that is called a "distal" demonstrative. We use this to refer to something closer to us ("proximal" is a fancy way of saying "close"), and we use that to refer to something far (distant) from us.

Now imagine the following scenario, with objects lain out as shown below:

Siu Ming

book 1

book 2

You

In this situation, imagine that Siu Ming says, "I think we should check this book."

Do you think Siu Ming is talking about Book 1, or Book 2?

Hopefully, you should interpret this as meaning Book 1. Book 1 is farther from you, but it's closer to Siu Ming. Since Siu Ming is the person speaking, you should interpet this and that based on Siu Ming's perspective.

To do that, however, you have to inhibit your own perspective. Otherwise, you might misinterpret "this" as referring to the book that's close to you (book 2), which is not what Siu Ming intended.

In fact, while adults usually have no problem understanding this kind of language correctly, young children are bad at it. Young children often misunderstand this and that in this kind of situation. Chu and Minai (2018) did linguistic experiments showing that children often appear to misinterpret demonstratives (e.g., the interpret "this" as meaning close to themself, rather than close to the person who's speaking). Furthermore, Chu and Minai found that children's errors probably wasn't because of a language issue; the children do know what this and that mean, so we can't just say "Children did poorly at the test because they didn't know the words". The real reason children didn't do well was because their executive function ability was not fully developed yet—Chu and Minai did psychological experiments to measure the same children's executive function ability, and found that the kids with the best executive function did the best on a task involving demonstratives. This, therefore, provides some good evidence that executive function plays an important role in language use and language understanding.

Example 2. Ambiguity

Imagine an incomplete sentence, "The scientist saw the planet with the..."

How do you think the sentence will continue?

People often guess something like "The scientist saw the planet with the telescope". I.e., the scientist used the telescope to see the planet.

But what if the sentence actually continues as, "The scientist saw the planet with the rings"?

These sentences have totally different structures. In "The scientist saw the planet with the telescope", the phrase with the telescope is describing how the seeing happened. If you have studied any formal linguistics and learned about syntax trees, you can think about how you would draw a syntax tree of this sentence. "With the telescope" would have to be attached to the VP ("saw the telescope") in this tree.

On the other hand, in "The scientist saw the planet with the rings", the phrase with the rings is describing the planet; it has nothing to do with the action of seeing. If you draw a syntax tree, "with the rings" would have to be attached directly to "telescope", not attached to the VP.

Now, keep in mind that when you read or hear a sentence, you don't get the whole sentence at once. The sentence unfolds over time. So, before you complete the sentence, there will be a moment where you have only read "The scientist saw the planet with the...". At this time, you might be expecting that "with the..." is a phrase describing saw (after all, "the scientist saw the planet with the telescope" seems to be a more commonly expected way to continue the sentence). When you suddenly then read the last word rings, you have to reinterpret the sentence. First you realize that rings is not something you can use to see a planet. Then you have to figure out that with the rings is not describing the "seeing" action at all, it is describing the planet.

To comprehend this sentence, then, you have to totally rearrange your understanding of the sentence structure. To accomplish that, you have to inhibit the your earlier understanding of what the sentence structure was, and you have to switch to another way of comprehending the sentence. These actions both require executive function.

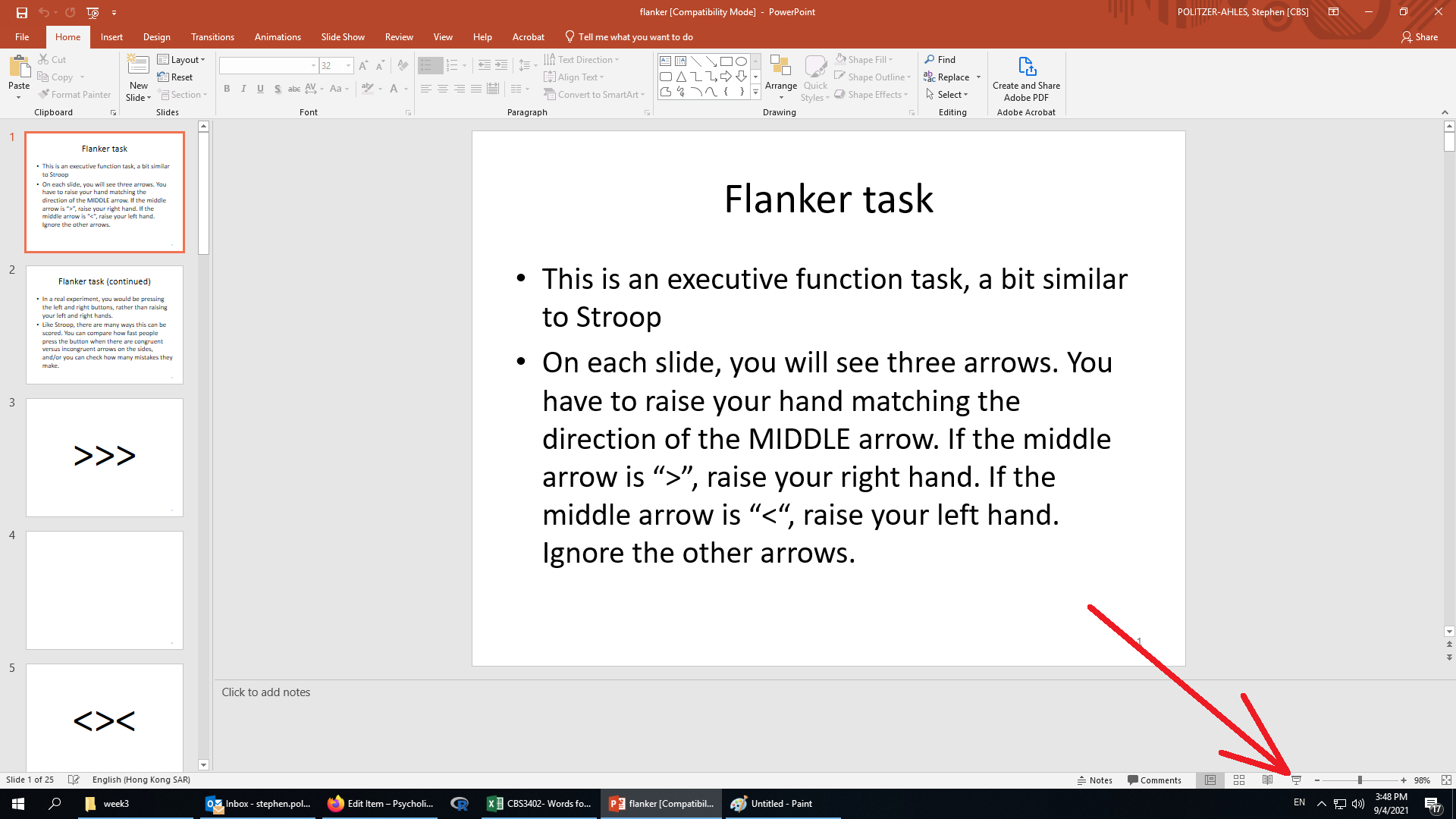

Other than the Stroop task, there are also many other tasks that also are difficult for people's working memory, and can be used to measure executive function in people. Try each of the attached demos to get a feel for different executive function tasks. Each of these is a Powerpoint slide show, beginning with some instructions and then showing a demonstration of the task. The best way to watch each slide show is in full-screen, by clicking the full-screen slide show button:

Here are the three tasks:

Note that each of these is just a mini demonstration, not a complete test; a real version of one of these tests would involve doing the task many times, not just once or twice like what's shown here.

After you've tried all the tasks, I want you to choose at least two executive function span tasks and write a brief comparison of their pros and cons. What do you think are some of the benefits of one task over the other? What do you think are some of the disadvantages? (Don't say a disadvantage of the Simon or Dimension Change Card Sort task is the use of colour; everyone says that, and it's too easy [i.e. it doesn't require thinking deeply about how the task works]. The same task could be done with something other than colour [e.g., size, filled vs. open shapes, etc.]. Try to think of some deeper advantages/disadvantages.)

When you have finished this task, go on to either of the other psychological mechanisms:

Or, if you have finished all three psychological mechanisms, go on to the last section of this module: "How to score cognitive tasks".

by Stephen Politzer-Ahles. Last modified on 2021-07-13. CC-BY-4.0.